When he was once asked if there was ever a case for using active “stock-picker” style managed funds, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Eugene Fama fired a question back: “Why do we pay people to do something they cannot do?”

So, what did he mean by that? Well, the market return is there for the taking: you simply need to buy a low-cost index fund. Yes, you’ll pay a modest ongoing fee for the fund, and there’s likely to be a small difference in your return compared to the market return (which may work to your advantage or may not). But, if you simply stay invested, you will be guaranteed to receive the average market return. And, because of the money you save in fees and charges, after costsyou will outperform the vast majority of investors.

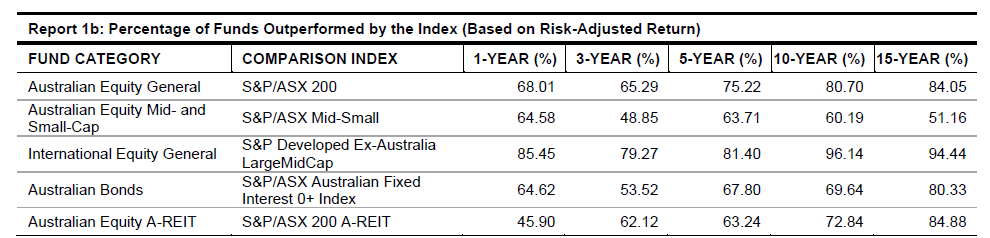

The only logic for using a stock-picker (active) fund over an index fund is that you think you will beat the market. You might, but the odds are very heavily stacked against you. The evidence tells us that only a very small number of active funds — somewhere around 1% of them — outperform in the long run (ie over an investing lifetime of say 30 yrs) on a cost and risk-adjusted basis.

It is true that over shorter periods, the odds of success are a little higher (see the SPIVA report data at the end of this article), but the longer you persist with active funds, and the more active funds you employ, the lower your odds of success become. Almost all the heroes of the investing world come undone eventually. Hamish Douglas of Magellan may be just another current day example.

The odds of picking a long-term winner,in advance, are therefore in the region of 100-1. And the more active funds you have in your portfolio, the less likely it is, overall, that you will outperform. Say, for instance, you invest in six active funds. The chances that every fund will outperform its benchmark index are about the same as picking all six winning lottery numbers.

It’s not exactly Mission Impossible, more like Mission Highly Improbable.

As Professor Fama would say, paying an active fund manager to try to beat the market is paying them to do something they almost certainly cannot do.

So why do so many people still use active managers? One explanation is that we don’t understand probabilities, and for many people that may be true. But it also has something to with how the human brain works, and how we often believe in things – because we want it to be so.

Last week I got an insight into an investment bank’s recommended portfolio for a particular client. At first blush, the portfolio was impressive – so many different fund managers; some newish boutiques and some other more established names.

As I worked through the list and checked the quantitative research for each fund, I could see that the track records over 5yrs were strong. However, in most cases the funds’ 1yr performance wasn’t as compelling. And herein lies the magic trick. This client had only been invested for one year. So, whilst the track record of each fund was sound at the time of the original recommendation (one year ago), the client’s lived experience was poor.

This investment bank’s approach is commonplace in the advice industry. The advisers claim the “value” in their service, and the reason you should pay their high fees, is the depth of their research and their “special skill” for picking stocks and funds. Their standard procedure is to pull together a recommended list of funds that have been superior performers in the previous period. This way, at the time the portfolio is presented, the recommended portfolio seems to have strong credentials.

In truth however, past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns. The academic research on this is endless. And as such, these kinds of portfolios, built of ‘yesterday’s heroes’, rarely deliver superior long-term returns in the real world.

In his book Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic, Gustav Kuhn, a psychology professor from Goldsmiths, University of London, and a keen magician himself, details a study in which people were shown video clips of magic tricks.

After one particularly amazing trick, researchers gave the group a choice: would they prefer to discover how the trick was performed or watch another trick. The result? 60% opted to watch another trick, while only 40% wanted to know how the trick was done.

There is, in fact, a growing interest in magic among psychologists and neuroscientists. What the research shows, is that, manipulating the mind, and getting it to believe the impossible, is frighteningly easy.

It isn’t because we are stupid that we don’t see something that is happening literally right in front of us, says Professor Kuhn; it’s because the brain is brilliant at economising.

“It’s purely about efficiency,” he says. “We have to filter out information to save energy, otherwise we would get overwhelmed. Rather than just processing all the information, the brain selects the stuff that’s really important. So, we can be looking at something right in front of our eyes, but the information doesn’t go any further and reach our conscious experience.”

Psychologists call this inattentional blindness. And it’s not just magicians who are clever at exploiting us. It also happens in business — especially in marketing and advertising.

The fund management industry uses the same techniques as magicians — misdirection, and the powers of suggestion — to exploit our cognitive biases and persuade us to buy its products.

When fund managers promote their products based on past returns, they are counting on our brains making assumptions and jumping to magical conclusions. Or put another way – they are counting on us extrapolating their past returns into the future. However, we know that past returns are not predictive of future returns. The academic research on this topic is endless. Some studies even find that the reverse is true. Yet our brains still try to latch onto that thread of hope through extrapolation.

It seems that we are hardwired, as human beings, to think that the past predicts the future. Psychologists suggest that this extrapolation to a favorable outcome gets our brains producing dopamine. So when we think this way, we are literally getting high from imagined wealth.

That’s right — dopamine, the same drug we crave when we can’t stop checking our mobile phones, when we keep putting money in a poker machine, or crave a giant slab of chocolate cake.

We know it doesn’t do us any good. But we do it anyway.

their relevant benchmark index.