For as long as we can remember, investors, the media and most retirees have misunderstood the concepts of income and cashflow. This may seem like semantics, but the distinction is important – especially for investors who partly, or wholly fund their lives from regular cash drawings from their portfolios.

Investors who fund their lives partly or wholly from their investments commonly take a view that they need to seek out investments that produce sufficient income to match their personal cashflow requirement. If their cashflow requirement is high relative to their investment base, then they look for high yielding investments.

These high yield investments commonly include high dividend paying stocks – like the big four Australian banks, and Telstra. And more recently, and because of declining interest rates – investors have sought out risky, unsecured credit investments (loans), that promise high income yields.

What these investors are trying to achieve is a situation where their investments, if left untouched, will provide a regular income that lines up with the cashflow they need to fund their lives. These investors are generally hopeful that if they only consume the income, then the underlying capital value of their investments will be maintained, or even grow, over time.

Whilst the ‘income logic’ here is faulty, and we will explain why, it is also somewhat understandable. Through our working lives, we get accustomed to living from our wages (income), and later in life we wish our investment income to be akin to the wages we once had. That is, a steady stream of money that meets our needs and tends to grow gradually through time.

But unfortunately, investment income isn’t always steady, and investments that provide high or very high levels of income, often come with trade-offs and unexpected risks.

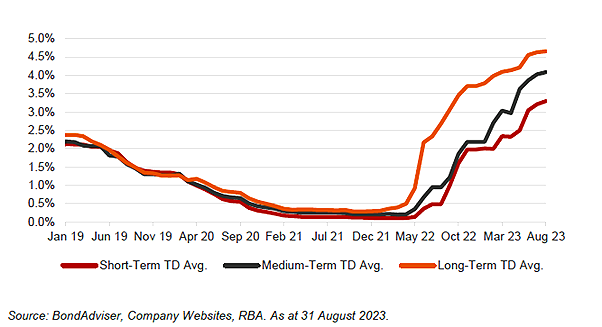

To begin with, let’s consider term deposits. These are often held up to be reliable, steady providers of income. However, if we look at term deposit interest rates in recent years, they’ve been anything but steady. See the chart below showing movements in the 180-bank bill rate (a proxy for six-month term deposit rates). You can see that as recently as 2021, rates were below 1%, whereas today, you can find term deposits paying 4.5% or more.

This kind of fluctuation in income would be seriously inconvenient if you were trying to fund yourself from this interest income alone.

Another common strategy, which is better, albeit still sub-optimal, is to build an investment portfolio comprised of high yielding shares, as well as term deposits – often an equal serving of each.

As the saying goes, the shares provide dividends, franking credits, and some growth, whilst the term deposits offer safety and stability.

But how well has this kind of strategy mix done really? Has it been safe, steady, and reliable? And was it sensible for these investors to consume all the income these portfolios produced?

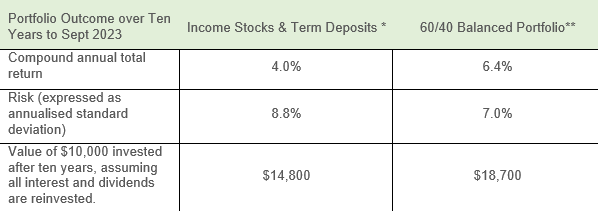

Let’s look at this question over the past ten years. For this analysis, we will consider two portfolios side-by-side. The first portfolio is comprised of shares in the big four banks and Telstra (equally held at 10% each), and term deposits (for the other 50%).

The second, more contemporary portfolio, is the academics’ ‘classic 60/40 balanced portfolio’. It is comprised of 60% growth assets (shares, property, and infrastructure) and 40% of defensive assets (bonds, credit, and cash).

** The balanced portfolio is made up of the following component parts: cash 6.0%, Australian credit 14.0%, global bonds 20.0%, international REITs and infrastructure 15.0%, Australian shares 30.0%, and international shares 15.0%.

Perhaps counter to what you may expect, the classic Balanced portfolio delivers both superior return, as well as lower risk (volatility).

The ‘cashflow’ required may be drawn from either portfolio, and it doesn’t so much matter whether that cashflow requirement be funded by portfolio income, or capital, so long as there is sufficient total return (ie income + growth) to meet the cashflow requirement. Let’s discuss in more detail…

Forget ‘Investing for Income’, there is a better way

An altogether better way to invest is to free oneself from the shackles of income thinking and focus on total return and cashflow.

Total return is the income plus the capital gains that your investment portfolio delivers over time. And cashflow, is the amount of money that you need to draw from your portfolio to meet your ongoing needs. It is important that your cashflow be carefully calibrated with your goals and your expected total return.

For example, if your portfolio is expected to deliver a total return of say 7% per annum over the longer run, and your goal is to maintain the real (inflation adjusted, purchasing power) value of your portfolio, then you can afford to draw a cashflow that is the equivalent of the total expected return (say 7%), less the expected long term rate of inflation (say 3%).

So, in this example, you can draw a maximum cashflow of 4% from the portfolio per annum. If you do this, then the portfolio’s real value should hold its value (ie the purchasing power).

Importantly, it matters not from where the total return comes from, either from income or capital gains, or both, is ok, so long as the total return of 7% is achieved. If this happens, then your goal of maintaining the portfolio’s real value will be met.

Asset Class Investing

A related and important concept is that of asset allocation. This is the process of setting a benchmark weighting for how much of your portfolio will be invested in each of the major asset classes, such as: shares, property, bonds, and cash.

Carefully calibrating your portfolio’s asset allocation is the surest way to establish a portfolio that will meet your total return (and risk) objectives. That is, how you mix the asset class components together will determine your expected total return, and the likely fluctuation of the return from year-to-year (i.e. the risk).

Portfolios that are more evenly balanced between risky assets (shares and property) and defensive assets (cash, deposits, and bonds) will produce more stable returns from year to year compared to those that have higher weightings to equities, or less diversification generally.

Whilst the classic balanced portfolio referred to previously will likely deliver a total return of around 7% over the long run, the respective asset class contributions to this return will vary materially through the economic cycle. In periods where interest rates are low, a higher proportion of the portfolio’s return will likely come from the growth assets, while the reverse may be true in periods of very high interest rates.

Similarly, each underlying asset class will deliver different returns at different times. Rarely will they all ‘sing in concert’. In most years, some asset classes produce good returns and others not so good. But the overall mix should provide a steady return that you can rely on to meet you cashflow needs.

An important concept here is portfolio rebalancing. This is the practice of regularly reweighting your portfolio to the asset allocation mix that you’ve set (including cash). It involves trimming the asset classes that have done well, and using those profits to top up the asset classes that haven’t done so well in the recent period. This is done with the understanding that each will have their moment at the top of the annual leader board, and their time further down in the rankings. So systematically selling high (when asset classes are toward the top of the leader board), and buying low (when they are toward the bottom), to restore your intended mix, can be a very helpful strategy for smoothing your returns, By employing this process, the investor also adds to the cash account, to top it up to fund the next series desired of cashflows.

Other confusing aspects of Investment Income

While we’re talking about the importance of distinguishing income from cashflow, it is worth mentioning a few other areas of common confusion.

It is often the case that investors mistakenly believe that they are consuming income, when in fact, they’re consuming a combination of income and capital.

Account-Based Pensions

Nowhere is this more prevalent than when retirees live from (consume) the money flowing from their superannuation pensions. That is, they mistakenly believe that this cashflow is income. But this is seldom the case.

The amount that superannuants are required, by law, to draw from their super pension, has no connection with the actual investment income earned from the underlying investments supporting the pension. In fact, the drawing rate is determined wholly by the age of the pensioner.

Sixty-year-olds, for example, are required to draw a super pension that is the 4% of their pension balance, whereas eighty-year-olds are required to draw an amount of 7%. In either case, it is unlikely that all the pension payment will be met from investment income. It is more likely, especially for the eighty-year-olds, that the pension will be funded partly from income and partly from capital.

But whether the pension is being funded from income or capital isn’t so important and shouldn’t be the investor’s primary focus. What’s more important is what the pension draw is compared with the expected total return on the underlying investment portfolio.

Recipients of superannuation pensions shouldn’t blindly consume all their pension cashflow, as this may or may not be appropriate, depending on their objectives.

For example, if you are 80, and your annual pension cashflow represents 7% of your pension balance, and you consume all of this – then it is likely you will see your capital base decline over time (in real terms). This may be ok for some, but many investors will wish to preserve their capital – and therefore they need to be mindful of only consuming the appropriate percentage that allows their portfolio to keep pace with inflation (most commonly closer to 4%). In these cases, any pension surplus drawn, should be reinvested elsewhere (perhaps in a personal portfolio) to maintain the overall investment base.

Managed Fund Distributions

Managed funds can be confusing as well. Often investors believe that the regular fund distributions they receive are income, but in truth, the distributions are often comprised of income and capital gains. This may seem odd, but managed funds are actually unit trusts, and as is the case with all trusts, they are required to distribute all their taxable income each year. And “taxable income” includes both income and realised capital gains.

So, in the case of actively managed share funds, if an investor was to consume all their distributions, they would likely be consuming both income and capital – and the value of their investment may erode over time.

Company Dividends

Even company dividends can be confusing. Many believe that the dividend they receive is the profits (income) that the company has made for the period, and that is generally true, but the dividend rarely represents all of the profit.

Companies vary in terms of how much of their dividends they pay out (called the ‘payout ratio’). Very few companies pay out 100% of their profits, as they generally need to retain some profits to fund their growth and other initiatives. This is partly why shares tend to appreciate, because some earnings are being retained and reinvested in the business.

Dividend Payout Ratios (another Income Trap)

Company dividend pay out ratios can confuse investors, especially those income focussed investors who often mistakenly believe that they can consume all of the dividend and the underlying stock price will grow to keep pace with inflation and more.

In truth, companies with the highest dividend yields tend to be the ones with the lowest growth profiles. These companies are generally mature, cash generative businesses with fewer opportunities for to grow.

A classic example is Telstra, which for a long time paid out most of its profits, and occasionally even more than its profits, as dividends. But alas, the company’s share price is still languishing at 2000 levels (ie its gone nowhere in 22 years).

Compare this to companies like BHP or CSL, which only pay out a modest portion of their profits but have grown their businesses enormously over the years. Over the same period (22yrs), BHP’s share price has risen eight-fold and CSL thirty-seven-fold. Moreover, whilst Telstra had a higher dividend at the start of the period (22 years ago), their dividend has remained much the same, whilst the other two have seen their dividends grow in line with their share prices, so the actual income received over the full period is much higher for BHP and CSL.

Summing up

So, when approaching your investment strategy, don’t constrain yourself by ‘income thinking’. Avoid the ‘income trap’, and instead, focus on total return, and managing your portfolio risk through sensible asset allocation. And be mindful of inflation, as it will affect your real return, and the amount of cashflow you can sensibly draw whilst still achieving your long-term goals.