Most investors can ‘feel’ that 2022 has been a miserable year. Australian shares, as measured by the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index are down around -7% year to date . US shares have fared even worse, with the S&P 500 Index down -22%.

Whilst this is a poor return, negative returns like this are not uncommon on the stock market, and most of us remember years that were much worse – such as 2008 when our stock market was down around -40% (peak to trough).

But looking at the returns of the stock markets alone belies what’s really gone on this year.

2022 has been one of those very rare periods where almost all capital markets (not just shares) have fallen in unison. Diversification (holding our investments across different asset classes – shares, bonds, and property) usually protects the shrewd investor from some of the market pain – this year diversification hasn’t really helped.

2022 has been one of the Worst Years on record for Balanced Portfolios – but don’t let Recency Bias override your Long-Term Strategy

Investing is easy when portfolio values are going up. We hardly notice the occasional market decline and, if we do, we might be tempted to view them as a buying opportunity. And that’s what investing is like in an average year.

However, 2022 has been anything but average. Markets have fallen almost from the very start, as bad news has kept on coming. We’ve had war in Ukraine, tensions with China, rising inflation and interest rates, a fuel crisis, and a cost-of-living crisis — not to mention increasingly bleak reports on the rate of climate change.

Such events are bound to have a negative impact on global stock markets, and that’s precisely what’s happened. But it’s what has gone on in the bond markets that has made 2022 particularly hard for investors.

Normally, bonds act as a shock absorber when equity prices fall. That’s because, in most times of crisis, the returns of stocks and bonds are negatively correlated. One goes up, and the other goes down; one zigs, the other zags.

Both stocks and bonds have fallen

But again, this hasn’t been a normal year. Both equities and bonds have fallen. Why? Because neither equity nor bond markets like unexpected bouts of inflation; and they dislike unexpected rises in interest rates even more. Even a small rise in interest rates, if it wasn’t widely foreseen, tends to have a negative effect on bond prices; in other words, prices fall as yields rise. Yet both inflation and interest rates have risen much faster than forecasters were predicting this year.

As a result, almost all investors have seen a substantial hit to their portfolios. These include the most adventurous investors, with 100% exposure to equities, and the most cautious, with all their funds invested in bonds. There was, in other words, nowhere for investors to run or hide.

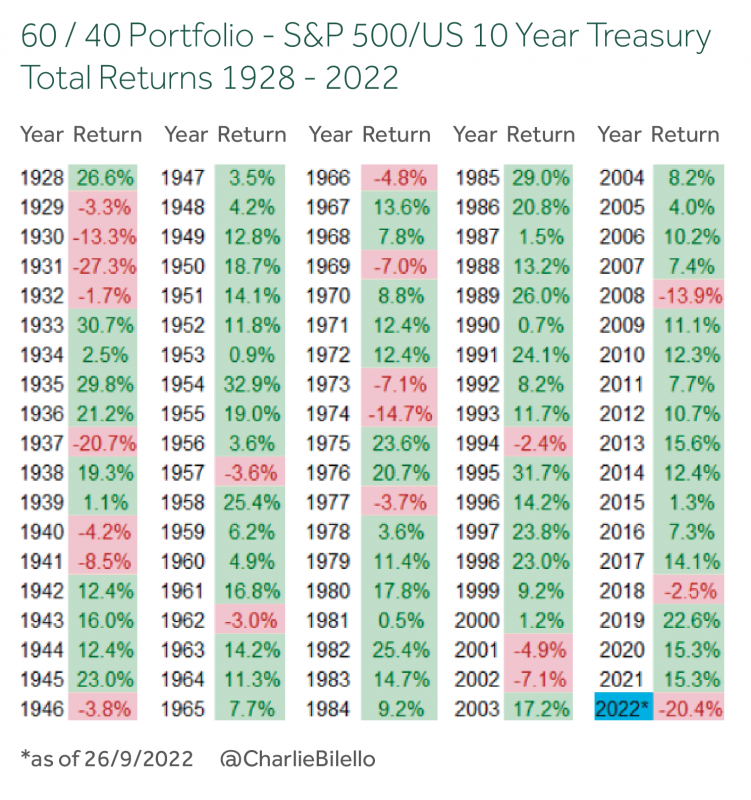

The chart below provides a perfect illustration of quite how exceptional 2022 has been. It was produced by US-based investment analyst named Charlie Bilello and shows the annual performance, since 1928, of a classic US-based ‘balanced portfolio’ with 60% exposure to the S&P 500 index and 40% to ten-year Treasury bonds. We are looking at the US data here, because we don’t have Australian data that goes back anywhere near as far.

As of the end of September, that US based 60/40 balanced portfolio had fallen 20% since the start of January. That’s the worst performance for a US based balanced portfolio since 1931. Put another way, what we’ve witnessed in the financial markets in 2022 is almost a once-in-a-century event.

Of course, the year is not yet through. The situation could improve between now and the end of December, or it could get worse. It is also true that Australian portfolios have fared better than the typical American equivalent – because Australian shares have held up better than American shares, and the AUD has fallen cushioning our returns on foreign investments. Either way though, there’s been no escaping the fact that the last nine months have been exceptionally tough.

Recency bias and loss aversion

Periods such as this tend to accentuate our behavioural biases, and two in particular:

The first is recency bias. Investors, in short, are far more influenced than they should be by recent experiences, and they assume that current trends will continue into the future. Right now, for example, when the financial pages are full of gloom, the danger is that we expect the status quo to last indefinitely.

The second bias is loss aversion. Simply put, loss aversion is the observation that investors dislike incurring losses more than they like making gains. So today, for example, investors who are smarting over the losses incurred in recent months may be less inclined to invest in the financial markers than they normally would.

The role of regret

A common strand that connects these two self-defeating biases is regret. We regret past decisions and any losses we feel we may have incurred because of them. And we are eager to avoid regret in the future. So, for example, we may want to wait to see the bottom of a bear market before we venture back in.

But regretting the part you feel you may have played in the losses you’ve incurred this year is illogical. Nobody has a crystal ball, and it is unrealistic to think, in hindsight, that anyone could have predicted with precision the events that have since unfolded — much less the impact those events have had on the markets.

Consider our own Dr Philip Lowe, Governor of the RBA, who said in November 2021 that he did not expect the bank to lift interest rates until 2024 “at the earliest” and that “the latest data and forecasts do not warrant an increase in the cash rate in 2022”. The RBA raised the cash rate in May 2022 and has increased it by 2.50% to October 2022.

Dr Lowe is incredibly well informed, experienced, and by all accounts a wonderful strategic thinker – but even he didn’t expect the onslaught of inflation that we have experienced this year (when it is precisely his job to forecast such things). So, is it realistic to think that you, or your adviser, could have seen these events coming? Surely, we are better to focus on the things we can control, than the things we can’t?

It’s also irrational to be overly focused on avoiding regret in the future. The key, as the Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman has explained, is to seek a balance between minimising regret and maximising wealth. That means planning for the possibility of regret and understanding clearly the range of possible outcomes beforehand.

Of course, there is no one right answer here and that’s because every investor is different. It’s also why it is so important to have an adviser who can map out the range of possible eventualities and test your reactions to each one.

Far more good years than bad

There’s no disguising the fact that 2022 has been a hugely challenging year for investors. But it needs to be put in its proper context. Good years for investors far outnumber the bad ones. And, if history is any guide, most of us may never experience as tough a year as this again.

The best advice, then, is to stay calm and rational. Sooner or later, the acute discomfort investors are currently feeling is bound to pass. So don’t let it derail your long-term strategy.